Home » Posts tagged 'Political Polarization'

Tag Archives: Political Polarization

3 simple strategies to sway people who don’t want to listen

Are Democrats just bad at communication?

Consider all the hand-wringing after the release of the Mueller Report. There were 448 pages of documented evidence of shady dealings by a presidential candidate and his minions before and after the 2016 election and the 2017 inauguration.

Before and after its release, Democrats in Congress, on talk shows, and in the press touted the findings of the Mueller Report virtually non-stop for nearly two years.

And the president’s approval ratings went from approximately 42% before the release of the report to approximately 42% afterward.

Does this mean that Democrats’ messaging about the contents of the Mueller Report was poor communication?

Not really.

There was a great deal of Democratic eloquence that was much appreciated by other Democrats. But that eloquence went unheard and/or unappreciated by just about everyone else.

If Democrats’ intent was to sway the opinions of people who were not Democrats, then the messaging was ineffective. Not necessarily bad. Just ineffective.

Why?

Well, if we divide the world of non-Democrats into two groups–Republicans and Independents–the messaging of the Democrats may have been eloquent but it was poorly constructed and targeted to reach those non-Democrat audiences.

Republicans tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Democrat messaging typically revolves around how wrong Republicans are. And not just wrong, but often evil, mean-spirited, uninformed, misled, immoral, and an existential threat to the founding principles of American democracy.

Who wants to pay attention to attacks on their character?

Independents tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Independents are just not very interested in politics, and especially not partisan politics (except when it smacks of scandal or World Wrestling Federation-style entertainment).

So, how could Democrats communicate their messages to these audiences? Here are three research-based* ways to reach people who just aren’t interested.

1. Repetition of Short Simple Phrases. Even when you’re not paying attention, things that are repeated over and over seep into your awareness. Once you’ve heard “Crooked Hillary” for the 1000th time, the words start to seem like they belong together.

“Most corrupt president in history” was a frequently repeated phrase at the most recent Democratic presidential debate. That might be a little too wordy and polysyllabic for maximum effectiveness, but the repetition is on the right track.

Repeated showings of video clips with repetitive messages like this one can also be effective, especially if captioned with an easily remembered phrase such as “He reaps what he sows.”

2. Emotionally Charged Images. Logic may be the favorite persuasive tool of intellectuals, but logical arguments never win the opposing side’s hearts. Emotional images avoid the logic trap. They stick. They also work best when combined with repetition and short, memorable phrases.

For instance, imagine the power of a photograph of one or more of the children who were separated from their parents at the southern border and held in cages? Imagine it shown with a caption of “Who locks up innocent children?”

Or a photo of a downcast Kurdish family in the ruins of their home with a caption of “Who abandons their allies?”

3. In-Group Tribal Spokespeople. Republicans don’t listen to Democrats, but they do listen to Republicans or people they believe speak for their view of the world. This makes Mitt Romney a potentially powerful figure in American politics as the year 2019 comes to a close.

Mitt may not speak to or for everyone, but thanks to the magic of videotape, other prominent Republicans can be used to deliver important messages to Republicans. One example is this clip of Senator Lindsey Graham describing what he considers an impeachable offense.

Can Sean Hannity or Rush Limbaugh be moved to speak truth to power, or about it? Stay tuned.

* If you’re interested in the research on which these suggestions are based, feel free to get in touch.

What happened to the middle?

1 = Strong Republican

2 = Not Strong Republican

3 = Lean Republican

4 = Independent/undecided

5 = Lean Democrat

6 = Not Strong Democrat

7 = Strong Democrat

We hear a lot about political polarization these days.

Editorial pages and pundits and Uncle Fred on his Thanksgiving Day soapbox express quite a bit of wishing that our politicians would pay more attention to the reasonable, norms-loving moderates in the middle.

But is there anybody there?

In his book, The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans (2009, U of Chicago Press) Matt Levendusky suggests that almost everyone has chosen up sides.

To make it easier for inattentive, unstudious, and busy-with-other-stuff normal folks to figure out which party more closely aligns with their worldview, party leaders have redefined and amplified the differences between what it means to be Republican and Democrat.

And, especially lately, they’ve also implied that the opposing party is an existential threat to “our” way of life.

Now, before you go “so I guess that means people should be more attentive and studious about politics,” there’s some convincing research suggesting that the more you pay attention to politics, the more partisan you get.* So maybe that’s been happening too.

Either way, while our sentiments may make us wish for a return to a comforting centrist sensibility in our national politics, it looks like we’re running short on centrists to lead that return.

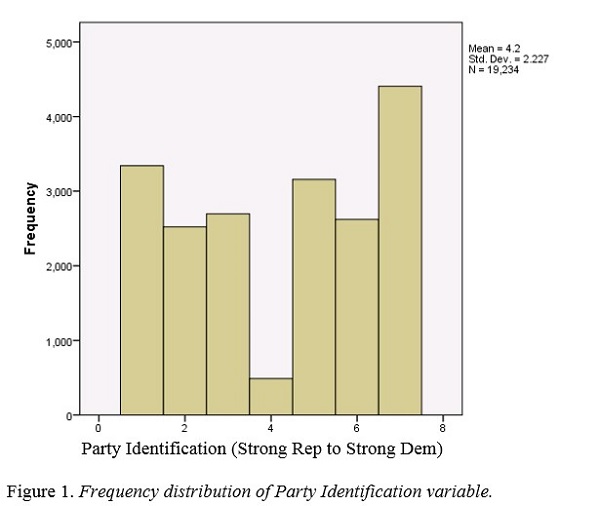

Normally, the distribution of almost anything along any continuum forms what is called a “normal curve,” with the fattest part in the middle of a relatively symmetrical arrangement of whatever population of people or things or other data points have ben measured. And the larger the population, the more “normal” the arrangement tends to be. The chart shown in Figure 1 was constructed using data from a recent American National Election Survey (ANES). It shows that, where politics are concerned, things are no longer normal.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the values for political party identification exhibited almost a perfect reverse of a normal distribution.

This may have been a function of the survey question, which asked respondents to identify themselves as one of the following: “Strong Democrat,” “Not Strong Democrat,” “Lean Democrat,” “Independent/other/undecided,” “Lean Republican,” “Not Strong Republican,” or “Strong Republican.”

Apparently, partisans did not seem to want to characterize themselves as “Not Strong.”

And hardly anyone was willing to be “Undecided.”

* Check out the work of Markus Prior