Home » Research

Category Archives: Research

Tell me a story about getting vaccinated

To test the effects of different vaccination advocacy message strategies on attitudes toward HPV vaccination, we randomly assigned study participants (N = 963) to one of four different message-strategy groups:

(1) The Narrative Strategy–A short story about a parent, Mark, who takes his 11-year-old daughter Emma to the doctor. During the visit, the doctor recommends that Emma receive the HPV vaccination. Mark is at first hesitant, but after considering the facts the doctor tells him, he decides to get Emma vaccinated. Afterward, they go for ice cream.

(2) The Informative Strategy–A fact-and-figure-filled overview of the case for HPV vaccination based on reports from the CDC, including the range of cancers the vaccination would prevent, the number of lives it would save, and its excellent safety record.

(3) The Expert Strategy–An appeal from a doctor with an impressive-sounding title asking for support in gaining acceptance for HPV vaccination, citing similar facts and figures from CDC reports. Accompanying the appeal was a photo of a distinguished-looking male doctor.

(4) The Non-Expert Strategy–An appeal from a school PTA member asking for support in gaining acceptance for HPV vaccination, citing the exact same facts, figures and rationale as the appeal from the expert doctor. Accompanying the message was a photo of a young mother with a small daughter on her lap.

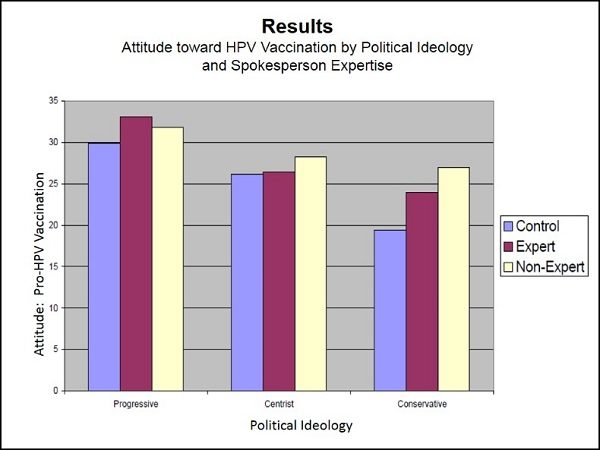

As illustrated in the graph above (Figure 1), when the vaccination advocacy messages focused on factual reasons for supporting HPV vaccination (as in the Informative, Expert spokesperson, and Non-Expert spokesperson message strategies), reactance (i.e., resistance) increased as transportation (i.e., emotional engagement with the message) increased. But when the message was delivered as a narrative story about one person’s HPV vaccination decision, reactance declined as transportation increased.

Resistance is persistent and problematic

HPV vaccinations are safe, readily available, and if universally administered would prevent countless cancers and save 4,000 or more lives in the U.S. every year. But at least 25% of the parents who receive vaccination recommendations from their doctors decline to have their children vaccinated.

Source: CDC (2019) Vaccine for human papillomavirus.

As the graph above (Figure 1) suggests, receiving vaccination advocacy recommendations from an informative source or an expert figure like a doctor produced significant amounts of resistance, with greater involvement in the message producing greater levels of resistance. Receiving those recommendations from a non-expert figure amplified this effect. But telling a story about a parent overcoming doubts to support HPV vaccination seemed to reverse this effect, with greater involvement in the story producing reduced amounts of reactance.

Analyses

The message strategies were modestly effective in producing positive attitude change: Post-Test Attitude – Pre-Test Attitude Mean Difference = 1.41 (SD = 3.81), t (935) = 11.34, p < .001. While there was no significant difference in attitude change between the messages, F (3, 932) = 0.79, p = .787, examination of the underlying factors contributing to attitude change revealed significant mediating effects of transportation and moderating effects of reactance.

While the direct effect of the different message strategies on attitude change was negligible, F (4, 931) = 2.08, p = .081, the indirect effect including the potentially causal mediating effect of transportation was quite significant, with greater levels of transportation producing greater change in attitude, t (933) = 2.75, p = .006. Greater levels of reactance, on the other hand, produced less and in fact negative change, t (933) = -4.92, p < .001.

Transportation vs. Reactance

With each of the typical persuasive message strategies that used facts and figures to achieve compliance with vaccination recommendations, as transportation (i.e., emotional engagement) increases, so does reactance (i.e., resistance), illustrated by the parallel lines that rise going from left to right in Figure 1. This increase in reactance limits the effectiveness of those messages to influence positive changes in attitude toward vaccination.

With the narrative strategy, on the other hand, increased emotional engagement with the story was associated with reduced reactance. This suggests storytelling may be an effective means for overcoming or avoiding resistance to vaccination when more directive strategies fail.

HPV Vaccination Background

Widely known to be the primary cause of cervical cancer, which kills more than 4,000 women in the United States each year (U.S. Cancer Statistics, 2019), HPV infection also causes cancer of the anus, penis and throat in men, and genital warts in both sexes (CDC, 2019). The infection is so widespread as to be considered of epidemic proportion. In the U.S., 80 million people (about one in four) are currently infected with HPV, 14 million more become infected each year, and nearly 35,000 people each year are affected by a cancer caused by HPV (CDC, 2019).

A widely available, easily affordable vaccine that would prevent 92% of HPV infections has been shown to be safe and effective (CDC, 2019), and the rational, socially responsible, utilitarian case for universal vaccination against HPV seems highly persuasive. However, acceptance and utilization of the vaccine have been far from universal. Barely half of 13-to-17-year-old adolescents in the U.S. are up-to-date on their vaccinations against HPV (Walker et al., 2019), and reports suggest that the percentage of parents actively choosing to resist having their children vaccinated against HPV is increasing (Darden et al., 2013.)

Explanations for the continued resistance and strategies for overcoming it are needed. The effects of reactance may be part of an explanation, and storytelling strategies may be part of the solution.

References

CDC (2019, August 2). Vaccine (shot) for human papillomavirus. Retrieved on March 17, 2021 from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/diseases/hpv.html

Darden, P.M., Thompson, D.M., Roberts, J.R., Hale, J.J., Pope, C., Naifeh, M., & and Jacobson, R.M. (2013). Reasons for not vaccinating adolescents: National Immunization Survey of Teens: 2008 – 2010, Pediatrics, 131, 645-651. Available online at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2013/03/12/peds.2012-2384

U.S. Cancer Statistics (2019, June). Leading cancer cases and deaths, female, 2016. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on November 2018 submission data (1999-2016). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Retrieved from https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html

Walker, T.Y., Elam-Evans, L.D., Yankey, D., Markowitz, L.E., Williams, C.L., Fredua, B., Singleton, J.A., & Stokley, D. (2019, August 23). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6833a2.htm

Marginal voters more likely to vote for Democrats in 2020

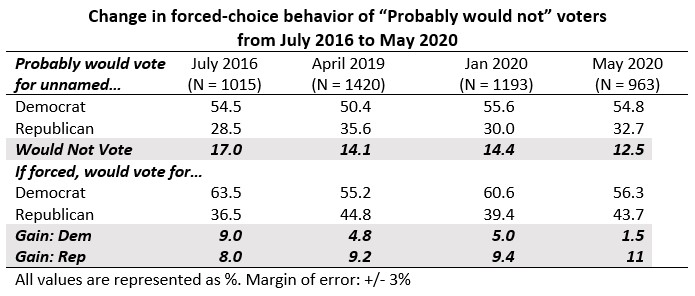

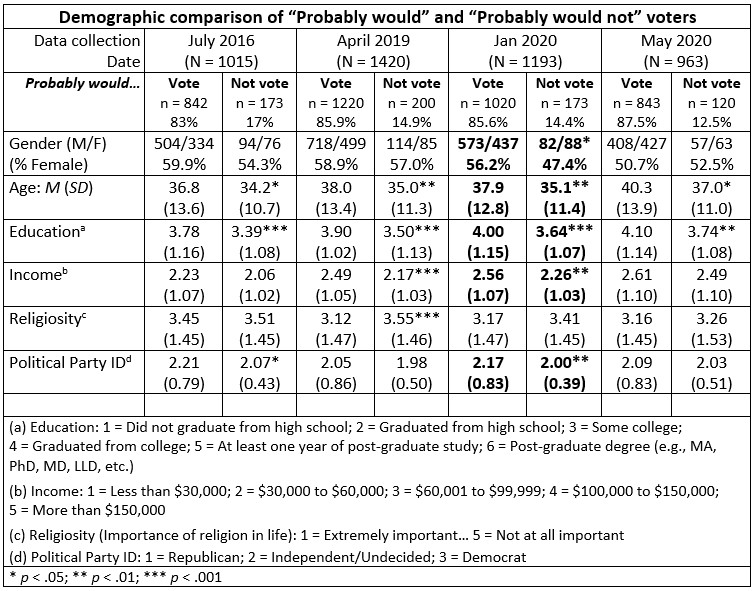

In four separate surveys conducted over the last four years, thousands of U.S. residents 18-years of age and older were asked to indicate whether they would vote for an unnamed Democrat or an unnamed Republican in an upcoming election some years in the future. Based on the trends suggested by these surveys, it appears more marginal voters are likely voting in the 2020 election, and most of them are likely to vote for Democrats.

The percentage of respondents who said they “would probably not vote” has gone from 17.0% in mid-2016 to just 12.5% in mid-2020. The party orientation of those who would probably not vote (determined by their indication of their vote-choice if forced to vote) suggests far fewer Democrat-leaning voters plan to sit out this election than Republican-leaning voters.

Adding the forced choices of “would-not-vote” respondents to the total vote counts adds just 1.5% to the total for the unnamed Democrat (from 54.8% to 56.3%) but adds 11% to the total for the unnamed Republican (from 32.7% to 43.7%).

Average voting percentages in Presidential elections in the U.S. have hovered in the 60% to 65% range for several decades. These results suggest an extremely high turnout for Democrats (i.e., 98.5%), with few opting not to vote. They also suggest a high turnout for Republicans (i.e., 89%), but with seven times as many Republicans remaining on the sidelines as Democrats.

[NOTE: Samples drawn from Amazon Mechanical Turk virtual workforce, which skews younger, more highly educated, lower in income than the average of the U.S. population.]

3 simple strategies to sway people who don’t want to listen

Are Democrats just bad at communication?

Consider all the hand-wringing after the release of the Mueller Report. There were 448 pages of documented evidence of shady dealings by a presidential candidate and his minions before and after the 2016 election and the 2017 inauguration.

Before and after its release, Democrats in Congress, on talk shows, and in the press touted the findings of the Mueller Report virtually non-stop for nearly two years.

And the president’s approval ratings went from approximately 42% before the release of the report to approximately 42% afterward.

Does this mean that Democrats’ messaging about the contents of the Mueller Report was poor communication?

Not really.

There was a great deal of Democratic eloquence that was much appreciated by other Democrats. But that eloquence went unheard and/or unappreciated by just about everyone else.

If Democrats’ intent was to sway the opinions of people who were not Democrats, then the messaging was ineffective. Not necessarily bad. Just ineffective.

Why?

Well, if we divide the world of non-Democrats into two groups–Republicans and Independents–the messaging of the Democrats may have been eloquent but it was poorly constructed and targeted to reach those non-Democrat audiences.

Republicans tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Democrat messaging typically revolves around how wrong Republicans are. And not just wrong, but often evil, mean-spirited, uninformed, misled, immoral, and an existential threat to the founding principles of American democracy.

Who wants to pay attention to attacks on their character?

Independents tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Independents are just not very interested in politics, and especially not partisan politics (except when it smacks of scandal or World Wrestling Federation-style entertainment).

So, how could Democrats communicate their messages to these audiences? Here are three research-based* ways to reach people who just aren’t interested.

1. Repetition of Short Simple Phrases. Even when you’re not paying attention, things that are repeated over and over seep into your awareness. Once you’ve heard “Crooked Hillary” for the 1000th time, the words start to seem like they belong together.

“Most corrupt president in history” was a frequently repeated phrase at the most recent Democratic presidential debate. That might be a little too wordy and polysyllabic for maximum effectiveness, but the repetition is on the right track.

Repeated showings of video clips with repetitive messages like this one can also be effective, especially if captioned with an easily remembered phrase such as “He reaps what he sows.”

2. Emotionally Charged Images. Logic may be the favorite persuasive tool of intellectuals, but logical arguments never win the opposing side’s hearts. Emotional images avoid the logic trap. They stick. They also work best when combined with repetition and short, memorable phrases.

For instance, imagine the power of a photograph of one or more of the children who were separated from their parents at the southern border and held in cages? Imagine it shown with a caption of “Who locks up innocent children?”

Or a photo of a downcast Kurdish family in the ruins of their home with a caption of “Who abandons their allies?”

3. In-Group Tribal Spokespeople. Republicans don’t listen to Democrats, but they do listen to Republicans or people they believe speak for their view of the world. This makes Mitt Romney a potentially powerful figure in American politics as the year 2019 comes to a close.

Mitt may not speak to or for everyone, but thanks to the magic of videotape, other prominent Republicans can be used to deliver important messages to Republicans. One example is this clip of Senator Lindsey Graham describing what he considers an impeachable offense.

Can Sean Hannity or Rush Limbaugh be moved to speak truth to power, or about it? Stay tuned.

* If you’re interested in the research on which these suggestions are based, feel free to get in touch.

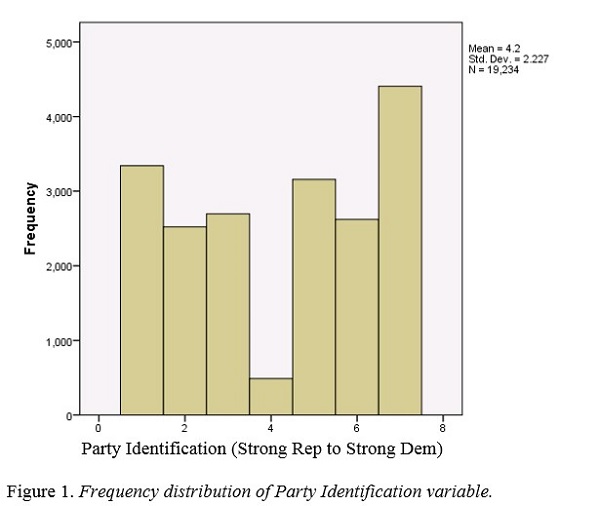

What happened to the middle?

1 = Strong Republican

2 = Not Strong Republican

3 = Lean Republican

4 = Independent/undecided

5 = Lean Democrat

6 = Not Strong Democrat

7 = Strong Democrat

We hear a lot about political polarization these days.

Editorial pages and pundits and Uncle Fred on his Thanksgiving Day soapbox express quite a bit of wishing that our politicians would pay more attention to the reasonable, norms-loving moderates in the middle.

But is there anybody there?

In his book, The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans (2009, U of Chicago Press) Matt Levendusky suggests that almost everyone has chosen up sides.

To make it easier for inattentive, unstudious, and busy-with-other-stuff normal folks to figure out which party more closely aligns with their worldview, party leaders have redefined and amplified the differences between what it means to be Republican and Democrat.

And, especially lately, they’ve also implied that the opposing party is an existential threat to “our” way of life.

Now, before you go “so I guess that means people should be more attentive and studious about politics,” there’s some convincing research suggesting that the more you pay attention to politics, the more partisan you get.* So maybe that’s been happening too.

Either way, while our sentiments may make us wish for a return to a comforting centrist sensibility in our national politics, it looks like we’re running short on centrists to lead that return.

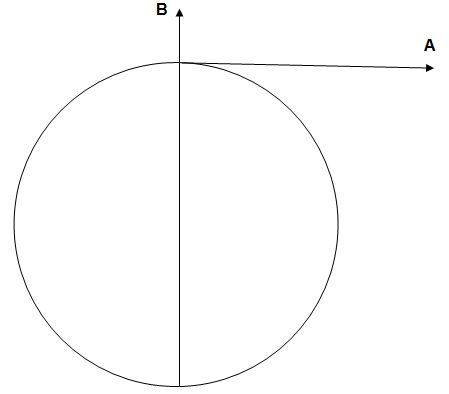

Normally, the distribution of almost anything along any continuum forms what is called a “normal curve,” with the fattest part in the middle of a relatively symmetrical arrangement of whatever population of people or things or other data points have ben measured. And the larger the population, the more “normal” the arrangement tends to be. The chart shown in Figure 1 was constructed using data from a recent American National Election Survey (ANES). It shows that, where politics are concerned, things are no longer normal.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the values for political party identification exhibited almost a perfect reverse of a normal distribution.

This may have been a function of the survey question, which asked respondents to identify themselves as one of the following: “Strong Democrat,” “Not Strong Democrat,” “Lean Democrat,” “Independent/other/undecided,” “Lean Republican,” “Not Strong Republican,” or “Strong Republican.”

Apparently, partisans did not seem to want to characterize themselves as “Not Strong.”

And hardly anyone was willing to be “Undecided.”

* Check out the work of Markus Prior

The Last Word on Improving Patient Satisfaction

You’ve improved your patient-care processes and outcomes but you’re still not happy with your patient satisfaction scores. And now, with CMS reimbursements increasingly tied to those scores, the pressure is rising to raise them.

Fortunately, the fields of psychology and behavioral economics may offer some easy-to-implement solutions to improve patient satisfaction scores both coming and going.

Start at the beginning

People’s memories are selective. They remember the beginnings and endings of things far more vividly and intensely than the middles.

The beginnings are particularly important, because they set up the patient’s expectations for everything that is to follow. It’s called “affect priming.”

If the beginning is stressful and unpleasant, the rest of the stay will have much repair work to do. Therefore, it is crucial to address patient satisfaction from the very beginning—the patient’s arrival at the hospital.

Address the parking situation: Worrying about finding a place to park is an issue that affects patients as well as their families. A free valet parking service can remove this worry and help create a caring first impression.

Careful maintenance of parking lots—to make them easily accessible, clean and safe— and liberal parking validation policies will also address this important opportunity to make a good first impression.

Greet everyone with a “Hello, can I help you?” Even people who spend a lot of time visiting hospitals can have a hard time finding their way around. Making every visitor feel welcomed and taken care of must become everyone’s priority.

Specially trained volunteers and/or dedicated staff “Welcome Ambassadors” can make a real difference in visitors’ experience.

Add some branded swag to the intake and admission process: In addition to making people feel welcome, giving them some branded items at intake can help them feel a stronger and more positive connection to you.

The act of accepting the gift of a branded pen (and/or other items such as tote-bags, socks, tee-shirts, baseball hats etc.) creates a sense of endorsement and mutual regard on the part of a patient. (It also helps if the intake and admission process is streamlined and friendly, of course!)

Your Last Chance

Research by Daniel Kahneman and Donald Redelmeier1 has shown the power of happier endings. They found that adding a period of greater comfort to the end of a painful experience influenced subjects to remember their pain levels as less intense.

Even when they made the overall unpleasant experience longer, ending it more pleasantly made the whole experience seem more pleasant.

The takeaway from this research is simple: Making the last few hours of a hospital stay more pleasant can change a patient’s lasting impression of the entire stay.

Here are a few last-day strategies that can pay big patient-satisfaction dividends:

Special last day meals: Food is always one of the most memorable (and not always pleasant) things about a hospital stay. Special meal treats on the last day before discharge, like an extra-specially made desert, can help make patients feel as though they have been treated with special care.

Special last day farewells: It is easy for a patient to feel anonymous, especially in a large institution like a hospital. Post the discharge schedule at all unit stations, and make it a priority for all members of every shift – and every discipline, including support and non-clinical personnel – to review the list and stop in to offer some “goodbye” best wishes.

The 30 seconds it will take will yield long-lasting and highly positive memories for the patient—and for your staff members as well.

Special last day treats and gifts: The same discharge schedule can be used as a distribution schedule for more branded swag items like those mentioned above in association with intake.

Tote bags are especially handy at discharge, especially if they are needed to carry some parting gifts—all carrying your hospital’s logo imprint, of course. Specially branded cookies and cupcakes (decorated with your logo as icing) can also help patients leave with good memories of their stay.

Health care includes showing you care

We’ve all seen studies that show that patients who have good communications with their care-givers rate the quality of care they receive higher. That’s another area worth focusing on for raising patient satisfaction scores (and certainly worth a few future posts).

Good communication makes for good relationships, and both circle back to the “affect priming” mentioned at the beginning of this post. If you show people you care about them on Day One, they will feel more cared about through their entire stay (and afterward, when they answer those HCAHPS survey questions).

You show you care by being interested—genuinely interested—in how they feel and what they have to say. Which means that it’s not enough to start off that first contact with, “Hello, can I help you?”

You also need to listen to what comes next.

References1

Kahneman, Daniel; Frederickson, Barbara L.; Schreiber, Charles A. & Redelmeier, Donald A. (1993) When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401-405.

Redelmeier, Donald A. & Kahneman, Daniel (1996) Patients’ memories of painful medical treatments: real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain, 66(1), 3-8.

Reducing Risky Behavior

Risk Communication Can Be Risky

Environmental Safety and Public Health Policy-Makers Often Make Matters Worse

Communication of science-based information to the general public…particularly health-related information…is a well-studied field.

This may be because it is so often done so poorly.

Many public behavior interventions, especially those based on intuition, “common sense,” political persuasion or religious belief, tend to focus on presenting a rational, logical argument for complying with a specific behavioral request.

Researcher Timothy D. Wilson cites “D.A.R.E.” and “Scared Straight” interventions…famous and widely adopted programs intended to reduce crime and drug use among young people…as examples of programs that “make perfect sense, but… are perfectly wrong, doing more harm than good. It is no exaggeration to say that commonsense interventions [such as these] have prolonged stress, raised the crime rate, increased drug use, made people unhappy, and even hastened their deaths.” (Source: Wilson, 2011, Redirect: The surprising new science of psychological change. New York: Little, Brown & Co.)

Unfortunately, this “boomerang effect” is too common in public policy communications. Public policy communicators would do well to read the government’s own manual on risk communication, which ought to be stapled to every keyboard in every PR department in every science, health and environmental organization in the English-speaking world.

Risk Is Attractive

Nike’s 5-minute animated World Cup commercial urges its audience to “Risk Everything,” basically because the safe route is boring. And clearly, there are a lot of risk-seekers out there.

While the animation and execution are exquisite, the storyline is predictable to the nth degree—but who cares? As an exercise in appealing to its targeted demographic: GOOOAAAAAALLLLLLLL!

The product shots are also very appealing. These are not the soccer cleats I wore in high school, and the shirts and shorts look as though world-cup-worthy pectorals, abs and glutes are included at no extra charge.

All this being said, the spot ought to be worrisome to conservatives, control freaks (including many sports coaches) and public health advocates. The reason it should be worrisome is not because of the spot’s likely influence on an easily-manipulated demographic—actually, soccer players are a rather stubborn lot. This spot is not going to change them in any way except maybe to increase their motivation to buy another pair of cleats.

No, the scarier scenario is that the spot is an accurate reflection of the risk-seeking ethos of an entire generation. In the spot’s storyline, risking everything is the only way to beat the practiced but predictable perfection of the clones (who could also be the minions of the Matrix, or the Man, or your parents).

But in real life, the associated behaviors are:

- Going for the low-percentage spectacular dunk rather than the safe but boring lay-up

- Riding the motorcycle without the helmet

- Not buckling those seat belts

- Not vaccinating your kids

- Not stopping to unroll that Trojan

- Not settling for the status quo

Small wonder so many campaigns aiming to reduce risky behaviors actually serve to increase them. Maybe the control freaks and health communicators would do better if they positioned those undesired behaviors as something other than risky.

How about stupid? Or shameful? Or embarrassing?

As Nike is trying to tell them, risky is just too attractive.

We may not pay attention to the data in front of us, but they do

Data Driven Marketing

Are we making our choices and decisions based on our own objective, rational, informed analysis of each situation?

Most of the time, probably not.

Here are links to a couple of interesting Ad Age articles that show what some marketers are paying attention to.

A case for responsive web design

In this article by Patrick Moorhead, shoppers who like to consult their smart phones about buying decisions are identified as more valuable than those who do their buying-decision-research at their desktops. BUT… not so much better as to suggest ignoring those desk-jockeys. (Like this one, for instance.)

All facts are not created equal

Are you driven by data? Or are you driven crazy by data? In this Kate Kaye interview with historian-turned-data-cruncher Kevin Lyons, it becomes clear that the ability to gather and present data is not sufficient to provide real value. Not when dealing with an exponential expansion of available data. The trick is finding the relevant data amongst all the irrelevancies and not-quite-relevancies. (Sounds like there is a lot of opportunity to fudge those numbers. Look for an up-coming post on “Lies, Damn Lies & Statistics.”)

The Politics of HPV Vaccination Advocacy

Who would YOU listen to?

A study of the influence of spokesperson expertise

My paper, “The politics of HPV vaccination advocacy: Effects of source expertise on the effectiveness of a pro-vaccine message,” was recently accepted for publication in the 71st Annual New York State Communication Association Conference Proceedings. The conference was held in Ellenville, NY, on October 18-20, 2013.

The paper received the conference’s award for Top Graduate Student Paper.

HPV (human papillomavirus) is a worldwide scourge that causes cervical cancer and thousands of deaths each year. Who do YOU think would be more influential in persuading people to support vaccination against HPV?

Most people would guess the authoritative-looking woman doctor on the left. After all, how much influence could a non-expert like the Middle School student on the right be expected to wield?

That was the focus of my study of spokesperson expertise.

Universal HPV vaccination would save more than 3,000 lives annually in the United States, and more than 350,000 worldwide. It makes sense. Its benefits seem almost inarguable. But there is a huge amount of opposition, largely distributed along political and ideological lines.

The intersection of health, science and politics

Mistrust and disbelief in evidence-based science and the recommendations of scientists are widespread and distributed along partisan lines. It is hard to prove any immediate life-and-death consequences to rejection of evolution or denial of the possibility of human agency in climate change. But with HPV and cervical cancer, the consequences are clear, present and immediate. We can document that partisan opposition to HPV vaccination is killing people right now.

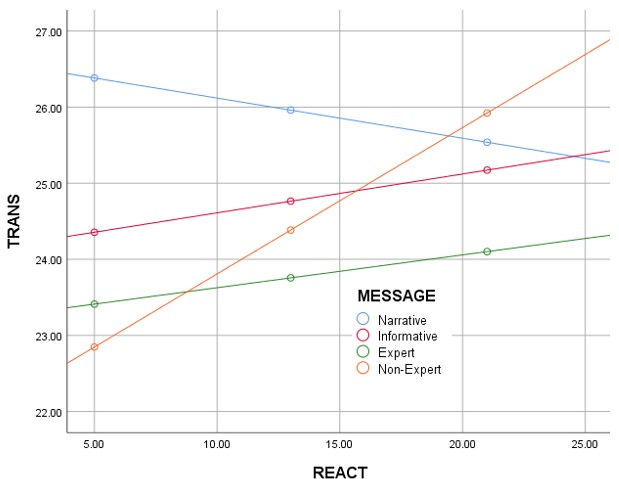

The results of my study suggest that people who are inclined to oppose HPV vaccination are more likely to listen to and be influenced by pro-vaccination messages from an obviously non-expert spokesperson (in this study, an innocent-looking middle school student) than from an expert (in this study, an authoritative-looking woman doctor).

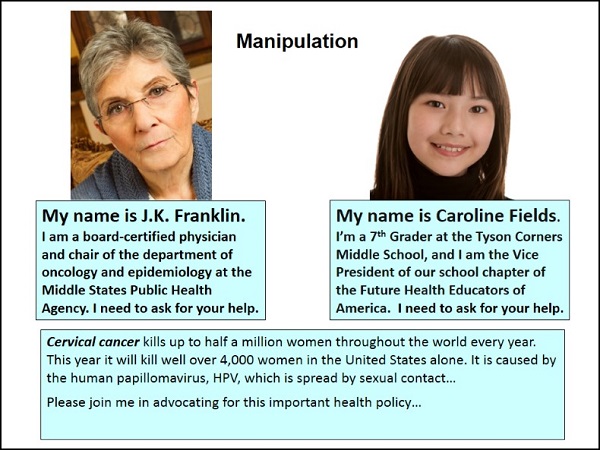

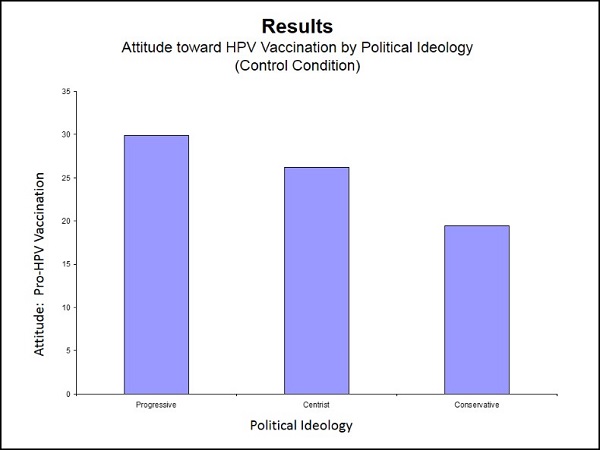

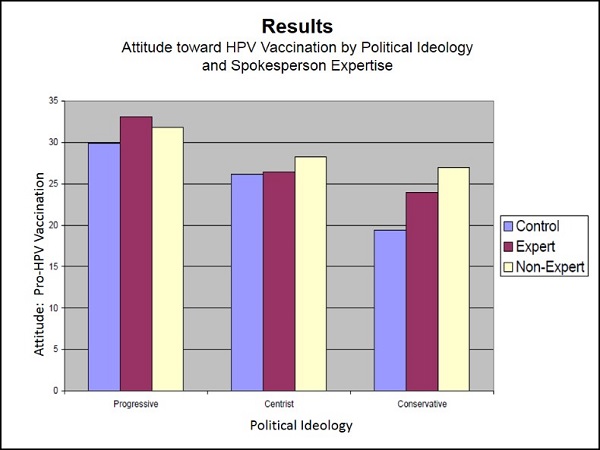

Three test groups: Expert, Non-Expert & Control

In my study, 474 adults were randomly divided into three groups. One group was instructed to read some basic, neutral information about the HPV virus and a pro-vaccination advocacy message attributed to the woman doctor.

A second group was instructed to read the same basic information about the HPV virus and the same pro-vaccination advocacy message, but for this group the message was attributed to the middle school student.

The third group (the control group) read the same basic information about the HPV virus, but received no advocacy message. Members of all three groups were also instructed to rate themselves politically as either Progressive, Centrist or Conservative.

After completing their reading assignments, the subjects were surveyed about their attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

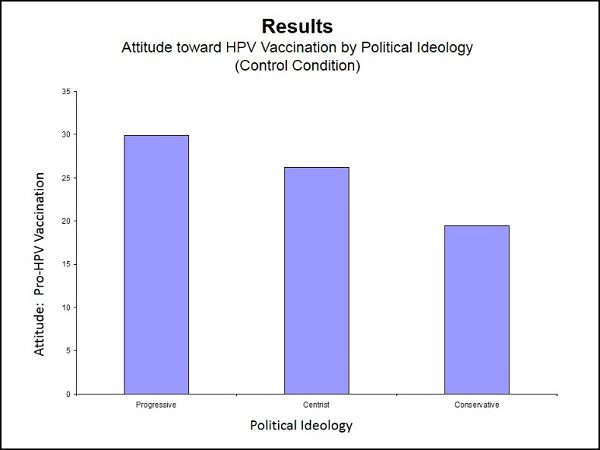

The attitude-scores of the control group (the ones who read only basic information but received no advocacy message) showed how attitudes toward HPV vaccination are skewed along partisan political lines. The more conservative the individual, the more opposed to HPV vaccination that person was likely to be.

Displaying the results for all three groups side-by-side (see chart below), it is clear that Centrists and Conservatives—those more likely to be opposed to vaccination—are more positively influenced by the Non-Expert spokesperson than the Expert.

For both Centrists and Conservatives, attitudes among those who read the advocacy message from the Non-Expert were significantly more positive than among those who received no advocacy message. There was no such significant difference in attitudes of those who read the advocacy message attributed to the Expert.

With Centrists, in fact, attitudes toward vaccination among those who received the advocacy message delivered by the Expert were virtually identical to those who received no advocacy message at all.

Among Progressives — who tend to favor HPV vaccination to begin with — attitudes toward HPV vaccination were more more positively influenced by the Expert than the Non-Expert.

Since virtually all pro-vaccination campaigns are spearheaded by people who favor vaccination, it seems likely that the tendency to rely on expert authorities as public advocates for vaccination may be the result of unexamined and untested assumptions that what influences Progressives will influence everyone. The power of spokesperson expertise may be overblown.

Overall, these results suggest that HPV vaccination advocates would be more successful if they would enlist more non-expert spokespeople in their public information efforts. The results also suggest that information about scientific and politically charged subjects might receive greater attention from doubters if the information is delivered by spokespeople who are not immediately identifiable as expert advocates for the other side.

Someone seeing the serious-looking doctor knows another authoritative persuasive argument is coming and tunes out before any persuasion can happen. With the non-threatening middle school student, there is more chance that the persuasive message will be heard.

Some persuasion is more effective than none!

A follow-up study suggested some interesting reasons for these results!

Reverse Psychology?

Yes, apparently you can actually get people to do something (or maybe NOT do something) by encouraging them to do the opposite.

There is a growing body of research that shows people can be discouraged from doing things they find pleasurable by paying them to do those things.

Theorists believe it demonstrates one of the major differences between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

When people do things because those actions give them pleasure or fulfillment, their motivations are intrinsic. Performing the actions becomes intertwined with their sense of identity: they do those things because of who they are.

When people do things because an outside force is compelling them to take those actions – by paying them, or forcing them or shaming them into it – their motivations are extrinsic. There is not the same kind of connection with the sense of identity.

With extrinsic motivation, there is often an undercurrent of resentment – psychological reactance – and a lost sense of freedom that can sap the pleasure out of an action that may have once been performed for fun. Extrinsic motivation tends to dampen and can even extinguish intrinsic motivation.

Putting this strategy into practice may be difficult, however. The chances of convincing any organization that must answer to public opinion to actually use this human tendency in an intentional way is pretty slim.

For instance, I don’t think we can convince the government that a good way to combat obesity would be to pay fat people to eat more.

But what about gun control?

Given the climate in the Republican-held House of Representatives, we are far more likely to pass a bill offering people financial incentives to own as many guns as possible than to pass a bill restricting gun rights in any way.

If we could get the government (i.e., the hated government, from which no good can ever come) to pay people to own guns, maybe this would work better to discourage gun ownership than trying to legislatively take away people’s right to bear arms.

By the way, on the subject of gun control, people on both sides of the debate could gain additional perspective on the matter by reading the classic science fiction novella, “The Weapon Shops of Isher,” by A.E. van Vogt.

Calling all racists

So you think we live an a Post-Racist Society? Well, what was your gut reaction to the title of this post?

I’m a fan of Cognitive Friction. It happens when you take two sets of facts or ideas or ways of looking at the world and you rub them together. For instance, many people think we live in a post-racist society, but the act of cognitive friction can reveal something very different.

The evidence of Harvard’s Project Implicit shows that the overwhelming majority of people in the United States – whites and people of color, young and old, rich and poor – harbor a deep-seated bias against darker skinned people. They persistently and unconsciously associate lighter skin on the positive side and darker skin on the negative side of the continuum on all the following sets of characteristics:

Smart vs Stupid

Good vs Bad

Safe vs Risky

Peaceful vs Violent

Lawful vs Unlawful

Beautiful vs Ugly

Likable vs Unlikable

Positive vs Negative

Okay, you might say, that may be true but it is just an unconscious bias that we all have learned to overcome because we do not agree with racism, we do not approve of racism, and we do not believe we are racists. Our conscious decisions about how we choose to act serve to mitigate and eliminate the effects of this racist bias. And it is, after all, our conscious choices that define us.

But if we rub the evidence of Project Implicit up against the evidence of a growing number of studies of elaboration likelihood (i.e., whether people are likely to engage in rational, conscious thought about something), we might start to worry.

These studies of conscious vs unconscious processing demonstrate that perhaps 95 percent of our actions are performed unconsciously, without intentional rational deliberation. Like the way we drive our cars, we mostly operate on autopilot. We may think we are thinking about something, but usually we are paying as little attention as possible while actually thinking about something else.

When these sets of findings are considered separately, there is little cause for alarm about the human condition, or about the persistence and pervasiveness of racism in the United States. But taken together, they suggest that even among people who abhor the idea of racism, 95 percent of their decisions and actions are undertaken under the unmitigated influence of a broad and deep-seated racist bias. Yes, racism is alive and well and we are all contributing to its expression.

Want to check your own degree of racism? Go to https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/demo/ and poke around.