Home » Politics

Category Archives: Politics

Marginal voters more likely to vote for Democrats in 2020

Surveys of people who said they will "probably not vote" suggest as many as seven times more Republican-leaning voters will sit out the election than Democrat-leaning voters. Continue reading

3 simple strategies to sway people who don’t want to listen

Are Democrats just bad at communication? Consider all the hand-wringing after the release of the Mueller Report. There were 448 pages of documented evidence of shady dealings by a presidential candidate and his minions before and after the 2016 election and the 2017 inauguration. Before and after its release, Democrats in Congress, on talk shows, […]

What happened to the middle?

We hear a lot about political polarization these days. Editorial pages and pundits and Uncle Fred on his Thanksgiving Day soapbox express quite a bit of wishing that our politicians would pay more attention to the reasonable, norms-loving moderates in the middle. But is there anybody there? In his book, The Partisan Sort: How Liberals […]

The Paradox of Political Humor

Q: Is political humor always anti-establishment? A: Only if it’s funny. Humor tends to be diminishing. When it diminishes others, it reflects poorly on the character of those who deliver it—unless they are professional comedians. And even then, it can be received poorly. Whether political or not, humor directed at people who are weak look […]

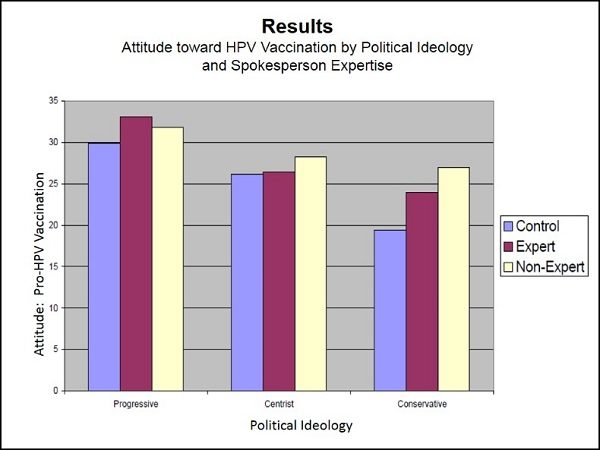

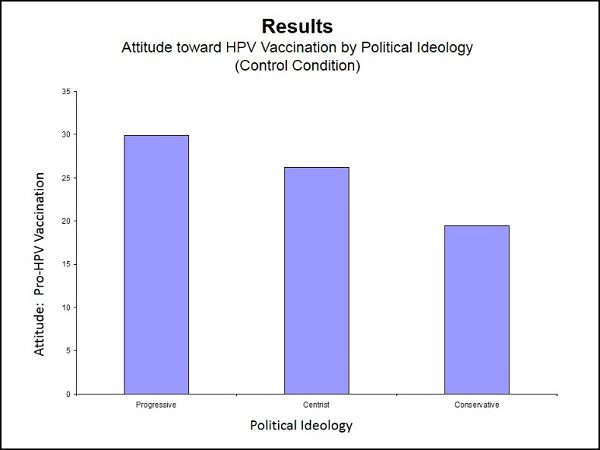

The Politics of HPV Vaccination Advocacy

Who would YOU listen to? A study of the influence of spokesperson expertise My paper, “The politics of HPV vaccination advocacy: Effects of source expertise on the effectiveness of a pro-vaccine message,” was recently accepted for publication in the 71st Annual New York State Communication Association Conference Proceedings. The conference was held in Ellenville, NY, […]

Reverse Psychology?

Yes, apparently you can actually get people to do something (or maybe NOT do something) by encouraging them to do the opposite. There is a growing body of research that shows people can be discouraged from doing things they find pleasurable by paying them to do those things. Theorists believe it demonstrates one of the […]

Calling all racists

So you think we live an a Post-Racist Society? Well, what was your gut reaction to the title of this post? I’m a fan of Cognitive Friction. It happens when you take two sets of facts or ideas or ways of looking at the world and you rub them together. For instance, many people think we […]