Home » Advertising

Category Archives: Advertising

On encountering another smartest person in the room

Are you in the right room? One of the problems with being the smartest person in the room is you too often expect no one else in the room will have anything of value to add, and that <sigh> you will have to expend soooo much energy getting those people who keep speaking up to […]

Reducing Risky Behavior

Risk Communication Can Be Risky Environmental Safety and Public Health Policy-Makers Often Make Matters Worse Communication of science-based information to the general public…particularly health-related information…is a well-studied field. This may be because it is so often done so poorly. Many public behavior interventions, especially those based on intuition, “common sense,” political persuasion or religious belief, […]

We may not pay attention to the data in front of us, but they do

Data Driven Marketing Are we making our choices and decisions based on our own objective, rational, informed analysis of each situation? Most of the time, probably not. Here are links to a couple of interesting Ad Age articles that show what some marketers are paying attention to. A case for responsive web design In this […]

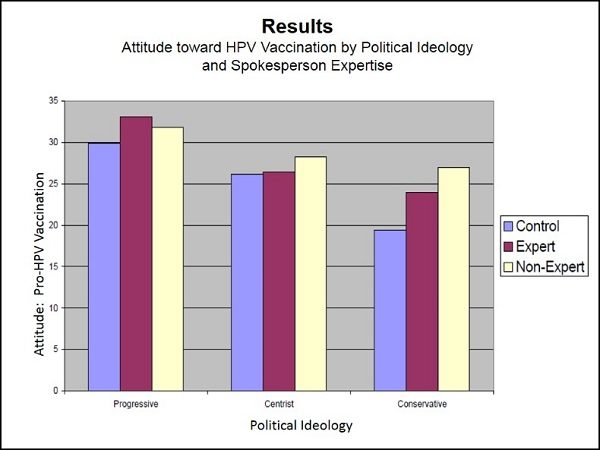

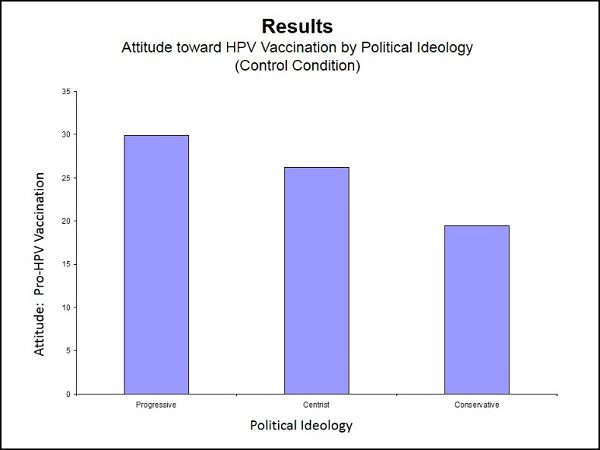

The Politics of HPV Vaccination Advocacy

Who would YOU listen to? A study of the influence of spokesperson expertise My paper, “The politics of HPV vaccination advocacy: Effects of source expertise on the effectiveness of a pro-vaccine message,” was recently accepted for publication in the 71st Annual New York State Communication Association Conference Proceedings. The conference was held in Ellenville, NY, […]

Lost on the information superhighway?

Writing for the web is not like writing for an ad Your objective is not to intrude on people’s lives and attract the attention of people who are busy doing something else. In web writing, your audience is actually busy looking for you. Here’s a little driving analogy. Suppose you are driving (without a GPS […]

So you want to be a writer?

Have you ever dreamed about the freelance writer’s romantic, adventurous, carefree existence? Me, too. But like in that movie, Nightmare on Elm Street, be careful what you dream. It might just come true. Now before we get into all that Freudian stuff, let me get a few things answered for you right away. There are people […]

Evolution & Marketing

What is the “marketing concept”? One of my students emailed me with a question about a working definition of “the marketing concept” for a homework assignment. Her textbook had not arrived yet, and she wanted to know whether the WikiAnswers discussion she had found online would be appropriate. After looking through my collection of marketing […]

Train Your Auto Pilot

The way even the most complicated software works is a bit at a time. Or a byte. Programs are made up of sequences of routines, which are made up of sub-routines, and the finished programs join them all together. My son taught himself to play the impossibly fast passages in Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet by breaking […]

Living on Auto Pilot

A few years ago, the company I was working for moved its offices from Troy NY to Albany NY. To get to the new offices, I needed to stay on Route I-90 all the way to exit 1 (I-87) instead of getting off at exit 7 (I-787), the turn-off for Troy, which I had been […]