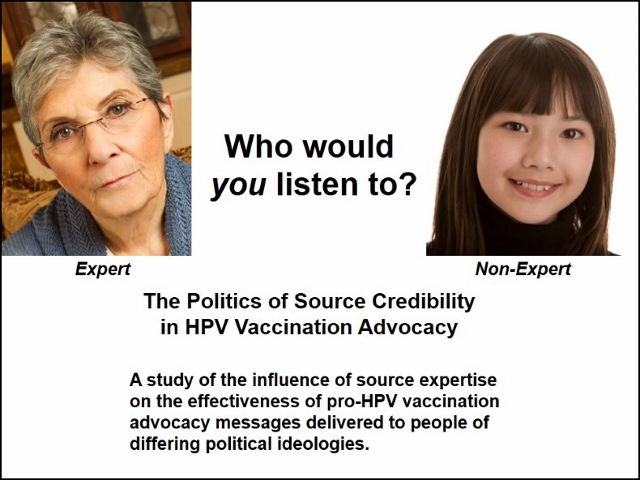

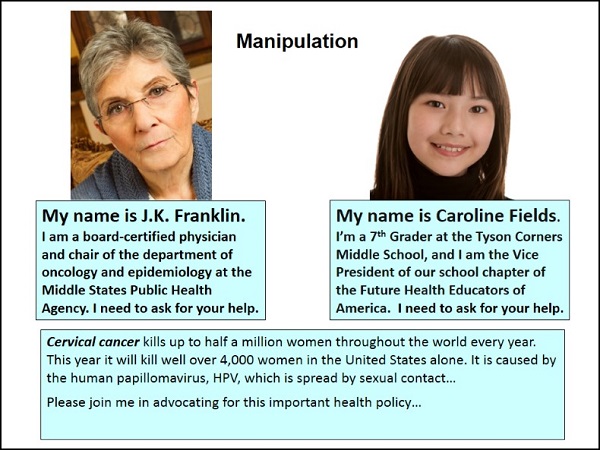

Who would YOU listen to?

A study of the influence of spokesperson expertise

My paper, “The politics of HPV vaccination advocacy: Effects of source expertise on the effectiveness of a pro-vaccine message,” was recently accepted for publication in the 71st Annual New York State Communication Association Conference Proceedings. The conference was held in Ellenville, NY, on October 18-20, 2013.

The paper received the conference’s award for Top Graduate Student Paper.

HPV (human papillomavirus) is a worldwide scourge that causes cervical cancer and thousands of deaths each year. Who do YOU think would be more influential in persuading people to support vaccination against HPV?

Most people would guess the authoritative-looking woman doctor on the left. After all, how much influence could a non-expert like the Middle School student on the right be expected to wield?

That was the focus of my study of spokesperson expertise.

Universal HPV vaccination would save more than 3,000 lives annually in the United States, and more than 350,000 worldwide. It makes sense. Its benefits seem almost inarguable. But there is a huge amount of opposition, largely distributed along political and ideological lines.

The intersection of health, science and politics

Mistrust and disbelief in evidence-based science and the recommendations of scientists are widespread and distributed along partisan lines. It is hard to prove any immediate life-and-death consequences to rejection of evolution or denial of the possibility of human agency in climate change. But with HPV and cervical cancer, the consequences are clear, present and immediate. We can document that partisan opposition to HPV vaccination is killing people right now.

The results of my study suggest that people who are inclined to oppose HPV vaccination are more likely to listen to and be influenced by pro-vaccination messages from an obviously non-expert spokesperson (in this study, an innocent-looking middle school student) than from an expert (in this study, an authoritative-looking woman doctor).

Three test groups: Expert, Non-Expert & Control

In my study, 474 adults were randomly divided into three groups. One group was instructed to read some basic, neutral information about the HPV virus and a pro-vaccination advocacy message attributed to the woman doctor.

A second group was instructed to read the same basic information about the HPV virus and the same pro-vaccination advocacy message, but for this group the message was attributed to the middle school student.

The third group (the control group) read the same basic information about the HPV virus, but received no advocacy message. Members of all three groups were also instructed to rate themselves politically as either Progressive, Centrist or Conservative.

After completing their reading assignments, the subjects were surveyed about their attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

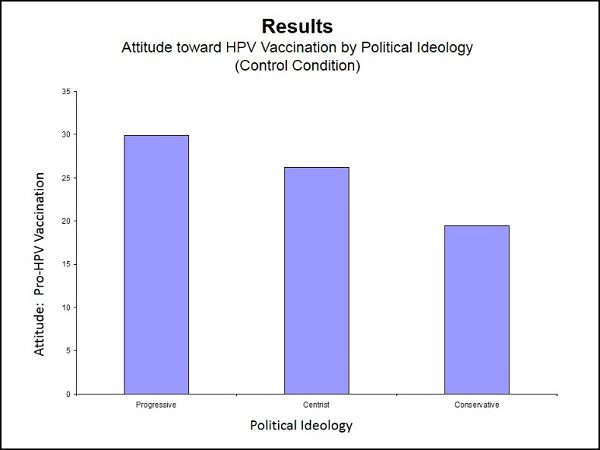

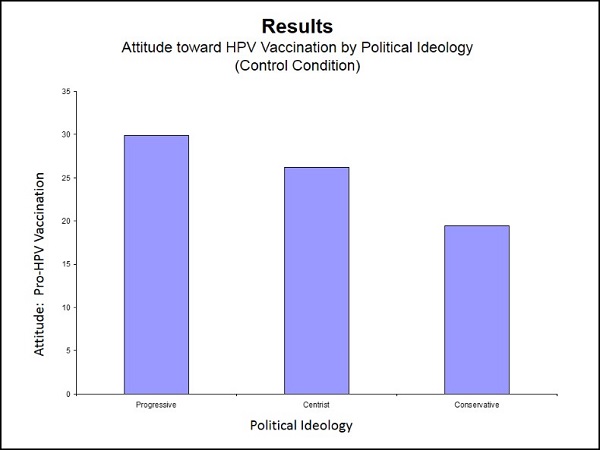

The attitude-scores of the control group (the ones who read only basic information but received no advocacy message) showed how attitudes toward HPV vaccination are skewed along partisan political lines. The more conservative the individual, the more opposed to HPV vaccination that person was likely to be.

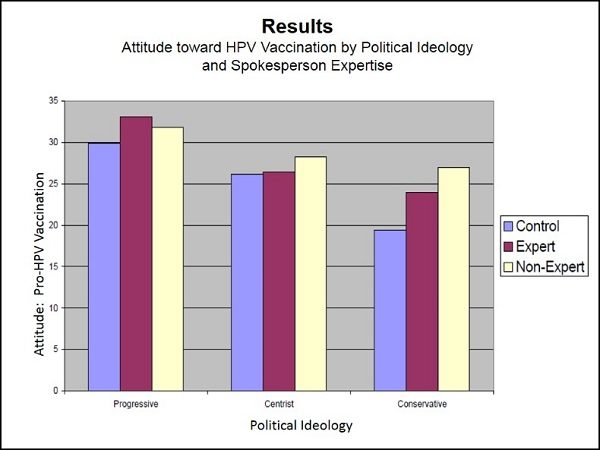

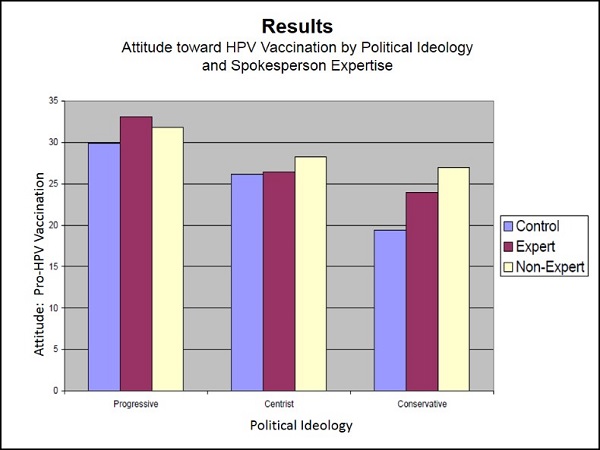

Displaying the results for all three groups side-by-side (see chart below), it is clear that Centrists and Conservatives—those more likely to be opposed to vaccination—are more positively influenced by the Non-Expert spokesperson than the Expert.

For both Centrists and Conservatives, attitudes among those who read the advocacy message from the Non-Expert were significantly more positive than among those who received no advocacy message. There was no such significant difference in attitudes of those who read the advocacy message attributed to the Expert.

With Centrists, in fact, attitudes toward vaccination among those who received the advocacy message delivered by the Expert were virtually identical to those who received no advocacy message at all.

Among Progressives — who tend to favor HPV vaccination to begin with — attitudes toward HPV vaccination were more more positively influenced by the Expert than the Non-Expert.

Since virtually all pro-vaccination campaigns are spearheaded by people who favor vaccination, it seems likely that the tendency to rely on expert authorities as public advocates for vaccination may be the result of unexamined and untested assumptions that what influences Progressives will influence everyone. The power of spokesperson expertise may be overblown.

Overall, these results suggest that HPV vaccination advocates would be more successful if they would enlist more non-expert spokespeople in their public information efforts. The results also suggest that information about scientific and politically charged subjects might receive greater attention from doubters if the information is delivered by spokespeople who are not immediately identifiable as expert advocates for the other side.

Someone seeing the serious-looking doctor knows another authoritative persuasive argument is coming and tunes out before any persuasion can happen. With the non-threatening middle school student, there is more chance that the persuasive message will be heard.

Some persuasion is more effective than none!

A follow-up study suggested some interesting reasons for these results!